Experience it in game

Play through the battle yourself in the immersive Company of Heroes 3 campaign.

Experience the dynamic campaign in game with

Experience the dynamic campaign in game with

Find out more

Find out moreIn the battle for Italy during the Second World War, Monte Cassino was not just a key strategic outpost for the Axis powers on the road to Rome – it was one of the strongest defensive positions in Europe.

Among the huge Allied coalition facing a gruelling uphill struggle to conquer this rugged mountain and its formidable defences, it was the Polish II Corps who finally broke the Axis line.

Amid the monastery ruins, after five months of heavy fighting, slow progress and strategic blunders, these brave soldiers proudly raised the red and white flag of Poland.

But Monte Cassino was just one chapter in an extraordinary tale of occupation, exile and fightback.

This is their story.

The ruined monastery at Cassino, Italy, 19 May 1944.

The Polish II Corps formed in 1943, the same year as Operation Avalanche and just a year or so before the battles at Monte Cassino.

By 1945, they comprised approximately 55,000 men and 1,500 women, incorporating units such as:

If you were to read a list of Polish soldiers at Monte Cassino, you would find troops from many different walks of life, and an array of religious backgrounds – Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Jewish.

Today, the resting place of many can be found at the Monte Cassino Polish war cemetery, along with the ashes and gravestone of their general, Władysław Anders.

The II Corps travelled a long, dangerous route from Poland to Monte Cassino – enduring the brutal Soviet Gulag and an arduous evacuation to the Middle East before they even arrived at the battlefield in Italy.

This saga ties closely to the history of their homeland, and its status in Europe at the beginning of the 20th Century.

Sherman tanks of ’C’ Squadron.

Poland was invaded again on September 1st, 1939, this time infamously by Nazi Germany – seeking lebensraum territorial expansion. As a result, the UK and France declared war on Germany, and the Second World War had begun.

A few weeks later, the Soviet Union also invaded from the east. Despite being ideological enemies, the German regime and the Soviets had agreed to carve up Poland and Eastern Europe between them as part of a secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact.

The people of Poland suffered brutal treatment at the hands of both regimes. In German-occupied territory, the Poles were considered untermenshen and were heavily persecuted.

The Nazis also began the systematic subjugation and extermination of millions of Polish Jews. By 1941, some of the most notorious concentration camps of the Holocaust had been built on Polish soil – including Auschwitz and Treblinka. Over the next few years, an estimated two million people were murdered in those two camps alone, while Warsaw became the site of Europe’s most notorious Jewish ghetto.

Meanwhile, eastern Poland was incorporated into the Soviet territories of Ukraine and Belarus. There, the feared NKVD secret police carried out the deportation and massacre of Polish army officers, civil servants and professionals in the forest of Katyn.

Others were rounded up and sent by rail to the Gulag in the far reaches of the vast Soviet empire – from Kazakhstan to Siberia – where they faced starvation, disease and brutal forced labour.

In one Siberian camp, 40% of the prisoners were said to have died in the first year.

For many Poles, their treatment led to lasting trauma – and vigilance. Matthew Parker notes how some survivors of World War Two were left with permanent fear of a further Russian invasion.

However, along with this trauma, there was also a deep-rooted desire among many Poles to fight back.

In 1941, the surprise German invasion of the Soviet Union – codenamed Operation Barbarossa – put a swift end to the fragile German-Soviet alliance. Now allied with the United Kingdom, Stalin agreed to release his Polish detainees and allow them to form their own army on Soviet soil.

General Władysław Anders was released from the NKVD’s feared Lubiyanka jail to lead the new force. Anders had fallen foul of the Soviet regime for fighting for Tsarist forces in World War One, and battling the Red Army in the Polish-Soviet conflict. He had faced years of interrogation, starvation, solitary confinement and torture.

But now, the resolute Anders called on "all able-bodied Polish citizens to fulfil their duty to their country and to join the banner of the White Eagle”.

.webp)

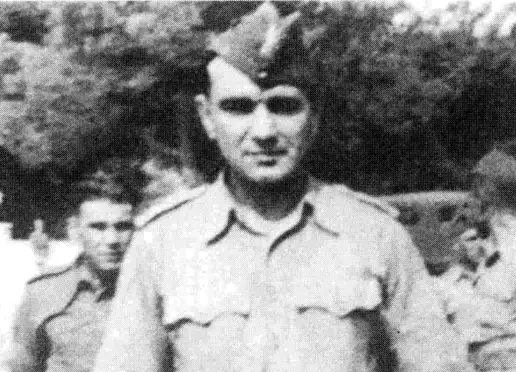

Polish II Corps: Władysław Anders during inspection of Polish high school in Casarano, Italy.

Experience the battle for yourself

Experience the battle for yourselfDownload the game now and see how the battle unfolded

In 1943, the Polish Corps landed in Taranto and joined a large Allied force taking on the Axis in Italy.

Italy was said to be ‘Hitler’s soft underbelly’, but breaking the rigorous defences on the road to Rome proved harder than expected.

The Gustav Line was a series of heavy fortifications that ran the width of the Italian peninsula. It made excellent use of the peaks, gorges and caves of the Apennine mountains, and was reinforced with machine gun turrets, barbed wire and mines. The area was “icy in the winter and baking in summer”.

Monte Cassino and its seemingly impossible obstacles formed the linchpin of the Gustav Line. If the Allies took this, the rest would crumble.

But it wouldn’t be easy.

Every move the Allied troops made seemed to be watched. The monastery took on an ominous, malevolent presence of its own: “You couldn’t scratch without being seen”, said one soldier. “And it was a psychological thing. It grew the longer you were there”.

After two failed attempts to take the position, British commanders demanded action to remove this obstacle. They directed waves of US bombs to flatten the monastery, despite dubious evidence of its occupation.

The bombings devastated the complex and killed 230 civilians. But while the cloisters, courtyards and statues were reduced to rubble and craters, the German forces, who indeed had not been using the monastery, quickly moved in and established defensive positions in the ruins.

Subsequent Allied engagements achieved little progress and suffered heavy casualties.

It was at this moment, with the Allies in disarray, that the II Corps were assigned the task of taking the hill once and for all.

If they were successful, it would not only achieve the seemingly impossible – the morale boost and propaganda victory for the previously-oppressed Polish units would be incalculable.

On 12th May 1944, the Polish II Corps advanced on Monte Cassino, with Anders eyeing a relatively gradual assault on the monastery. Rather than heading straight towards the target and risking enemy fire, his troops would steadily take positions on the high ground beyond the ruins.

The Polish Corps were hungry for the fight. According to Matthew Parker, as they ascended the hillside, one British eyewitness noted how he’d “never seen anyone so full of hatred. All they wanted to do is kill Germans”.

As they marched, they were subject to propaganda through loudspeakers – urging them to surrender, join forces with Germany and take the fight to the Russians.

It is safe to say this did not work.

On their way to their attacking positions at Monte Cassino, the Polish troops noted the stark ruin of this once idyllic Italian hillside – the product of months of grinding battle.

Soldiers of the Polish Army.

Following the grim ascent, the attack itself was fraught with danger. The Kresowa Division would be tasked with taking the feared Phantom Ridge, while the Carpathian Division made ready to secure the infamous Hill 593 – which was “full of German bunkers”.

It was now or never. The Polish army’s attack on Monte Cassino was supported by a heavy artillery barrage of around 1,600 guns at 23:00 hours the previous night. At 01.30, the troops began their assault.

Stefan Orzechowski from 5th Kresowa Infantry Division, Italy, 1944

Stefan Orzechowski: Historia walk 5 Kresowej Dywizji Piechoty / CC BY-SA 4.0

The Polish troops then launched their second offensive – aiming to distract the Germans from the British advance and take the monastery once and for all. Anders again sent units to capture the dreaded Phantom Ridge and Hill 593.

It was time to seize the monastery.

Expecting a violent climax to the battle, Anders and the courageous Poles prepared for the worst. However, what they did not realise was that German Commander Albert Kesselring had already ordered a withdrawal from the ruins, sensing impending Allied victory.

After a nerve-racking scout of the area, the Polish Corps realised the battle was won.

They hoisted the Polish flag proudly, along with the Union Jack in honour of their British Allies. One soldier even played the traditional Polish bugle call of the Krakow Hejnal to commemorate the victory.

In the space of just a few years, Anders and his heroic forces had journeyed from captivity, brutalisation and the brink of starvation to conquer a mountain, and capture one of the most formidable defensive positions on the continent.

It was an incredible moment for the whole of Poland – but one that came at a terrible price.

©Relic Entertainment. All rights reserved. Developed by Relic Entertainment. Entertainment, the Relic Entertainment logo, Company of Heroes and the Company of Heroes logo are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Relic Entertainment. Relic Entertainment is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. All other trademarks, logos and copyrights are property of their respective owners.